I recently asked our Stanford ’70’s alum e-mail group to recount their experiences with the draft. Here’s a wonderful memoir from classmate John Landon.

Gulf of Tonkin

The end of Nineteen Seventy.

A recent, undistinguished graduate of a distinguished University, I was living down near the Bayshore Freeway on both sides of San Francisquito Creek, the primary water source for Rosottie’s Beer Garden and the dividing line between Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties. On the north side of the creek I was living in Ken Kesey’s old house and, to the south, I rented a room in a house occupied by another group of former students, living and dancing the reclassification limbo mambo. The Santa Clara based fodder was given induction physicals in San Jose. The San Mateo group of patriots was invited to the Oakland Induction Center. I had been blessed with a draft number that assured my induction if I was reclassified in 1970 and virtually assured a pass if the bureaucratic deed occurred in ‘71. Three or four physicals rescheduled and therefore delayed due to the jurisdictional confusion caused by the uncertainty over my true residential status finally elicited a summons that stated that my Uncle Sam didn’t really give a shit about the niceties of my actual residence and that I had better get my slacking ass to Oakland Induction Center on December 17th with a tooth brush and clean underwear, or face something worse than getting shot in a jungle.

At that point I played my one and only trump card. A little known statute stayed any reclassification action on any individual with a pending application to the Peace Corps. My completed app hit the mailbox the next day. The grace period was only fourteen days; just enough to delay my reclassification date to a bleary, hung over 1/2/1971. The efficacy of the application was celebrated but the essence was quickly forgotten.

Three months later, still dithering about Grad School, a real job and other life changing commitments, the much-maligned Federal Government made me an offer I could not refuse. Two years surveying and mapping mountain villages in the essentially unexplored, central Himalayas; Shangri-La on a government pass. Typical of the place and time, I had no surveying, mapping or engineering experience.

With vague notions of James Hilton and Joseph Conrad, I stepped on the bus.

For eighteen months I tramped through triple canopy jungles, climbed twenty thousand foot ridges and camped in fourteenth century villages with only my bamboo rod, my fifty-foot chain and a hand held transit. I lost fifty pounds to disease and malnourishment.

I found an unexpected facility for languages, finally speaking fluent Nepali with a western hills twang.

During my travels I also carried a long, sharp kukri, the local machete, which came in handy during the ritual animal sacrifices I performed. I was a goat specialist; anything larger, a water buffalo, for instance, was beyond my expertise. Anything smaller, i.e. a chicken, was beneath my dignity and station as the giant, red-haired ferengi, who might build a water system in the village someday. Also, as the all purpose repository of western magic, I was occasionally called in to save stillborn babies, most unsuccessfully, although in an upset, I was often able to save the mothers through my innovative use of clean cloths and plenty of hot water; basic techniques I learned from Doc and Kitty on Gunsmoke. I was asked to explain why anyone would go all the way to the moon. Anyone could see, on a clear night, that there was nothing there. I was asked if I knew the King, an accusation I vehemently denied. He was a Harvard man, later machine gunned by one of his drug-addled sons.

My denial of the King’s Deity may have been a seed that grew into the successful Maoist revolution that was just completed in the area. More likely it was the general malfeasance of his and the successive governments of his family rule.

The water systems that were eventually built saved many lives. The incidence of malaria and dysentery in the area were slashed. Birth survival rates more than tripled, from 20% to 60%. Of course that led to overpopulation and massive deforestation. The jungles I hiked are all gone, burned for firewood to feed all the new babies. The tigers and bears that roared in the night are all gone. Only the yetis still roam the barren mountains, sometimes howling in the darkness.

When I returned to America, six months short of the full two years because Dick Nixon cut off all Peace Corp funding, in a preventative strike against one Kennedy or another, Terrell and I, along with another friend, built a bar and called it The Dead Goat Saloon. I considered an animal sacrifice at the grand opening but thought that it might be a little over the top.

My boats have all been named Kathmandu and my books all have an element of mysticism.

And that’s what the Tonkin Gulf Resolution means to me.

John Landon

Dear John,

Thanks so much for your wonderful recounting of your experience of our collective post-graduation dilemma vis-à-vis the draft. After several readings of your adventures I decided that most of what you recounted could have taken place in the Himilayas in the wild and woolly early seventies. But I knew Baron Munchhausen had a hand in your tale when I got to the part about the subsequent burning of the forests. To wit: "The jungles I hiked are all gone, burned for firewood to feed all the new babies.” Come on, John. Even in the Baron’s fanciful world, he never would have imagined that Nepalese babies were being fed burned firewood… I’m totally down with the yetis though...

My own draft tale is sadly, from a story-telling P.O.V., much more pedestrian than yours, but at least no forests were burned on my account, nor wild mega-fauna slaughtered. Like all of us, I got the dreaded “Greetings:” letter from General Curtis Lemay, the head of the U.S. draft. I can still see us all that fateful night our senior year, gathered around the television for the first ever draft lottery. The news media had assured us that anyone with a number below 230, I think it was, was sure to go. (Like lambs to the slaughter, anywhere that Curtis went; the lambs were sure to go…). My number came up 166 so I knew I was potential future canon fodder.

When the sorrowful day came, we all dutifully lined up like the little lambs we were, boarded buses and headed for the Oakland Induction Center. The building itself was cavernous and intimidating. Large, concrete and bereft of any personality, it resembled nothing so much as a maximum security prison. Inside, the long hallways were institutional lime green and ivory. The linoleum floors were similarly dreary and unremarkable except for one feature. They had a yellow (as memory recalls) line painted down the center. We inductees were instructed via loud speaker, (halloo, George Orwell!) to follow the yellow line to the next induction station. (caution: this yellow brick road will not lead to The City of Oz). At one station each of us in turn was closely eye-balled, followed by a close inspection of our ears, noses and throats. At another station we all were told to drop our trousers and a young rubber gloved medic reached into our underlings, gently took our scrotums in hand, and instructed each of us to cough. I guess they were looking for carriers of testicular tuberculosis… Another fun E-ticket ride was the bend-over digital rectum probe. I seem to recall they also examined our teeth and the arches of our feet. No expensive future dental bills or fallen arches in this man’s army!

After our serial humiliations were over, we were individually ushered into small windowless rooms with two chairs, a desk and one doctor. My doctor was an avuncular looking fellow with thinning grey hair and rimless spectacles a la Robert MacNamara. He somberly ushered me to my seat and opened a manilla folder. “I see here by your medical records you had a five hour experimental open chest surgery to repair a congenital case of pectum ex cavitum, performed in 1959 at Queen’s Hosptial in your home town of Honolulu, Hawaii. Is that correct?” I answered in the affirmitive. “It states further in these records that Drs. Mason and Gebauer postulated that because of the experimental nature of the surgery, it was questionable whether you would retain sufficient vital lung capacity to perform normally during periods of peak physical stress. I am directing you to return to Stanford and report to the Palo Alto Medical Clinic for a respiratory test. If this physical restriction is present today, that may be grounds for reclassification to 4-F” (Fit only to serve in times of dire national emergency.) He closed the file, looked up at me and a gentle smile crossed his face. “Good luck, son. I have a boy about your age. He graduates college next Spring.” I found out some years later that my father, who was also a doctor, though of the psychiatric sort, had had the foresight to get my chest surgeons to include the bit about my “questionable peak vital capacity”. He was imagining a day when we might get involved in just such an embroglio as the Vietnam war and he wanted me to have a chance at “opting out”.

Now I was not only a member of the Stanford Varsity Volleyball team. My senior year I was the captain of the team. After practise, my fellow teammate and buddy JB and I would run down to the old cavernous wooden stadium and run the stadium stairs. Up and down, ten times in a row as fast as we could go. I wouldn’t have been voted captain by my teammates if I had exhibited signs of not possessing "peak vital capacity” necessary to lead our team into the NCAA Volleyball Championship Tournament our senior year. The fact that we came in last of the five teams competing had nothing to do, I steadfastly maintain to this day, with my peak vital capacity...

With doctor’s orders in my sweaty little fist, I hastened to the Palo Alto Medical Clinic. There I was weighed and measured and asked if I smoked. (three to five cigs a day, I replied). I was then hooked up via a plastic tube taped to my mouth, to a large cylinder half filled with water within which floated another cylinder. There were calibrations on the side of the outer glass cylinder measured in mili-liters. “Now son”, said the doctor, “I want you to blow as hard and as fast into this cylinder as you can until I tell you to stop. The amount of air you displace determines your peak vital capacity as measured against what it should be based on your height, weight and smoking habit."

As a soon-to-be Stanford graduate I was just smart enough to know I didn’t want to huff and puff till I blew the house down. I wanted to respire just enough to make it look like I was trying but not enough to get me inducted. In other words, too little huffing I could be indicted. Too much puffing and I could be inducted. I was directed by the Induction Center to report to Letterman’s Hospital in the SF Presidio with the results of my test. The doctor made a show of ceremoniously sealing up a large manilla envelope that had my test results in it along with chest x-rays. I did get a glance at the records before they were sealed and saw that I had tested out at 49% of what my lung capacity should have been based on height and weight, etc. “Uh oh”, I thought to myself, "I may have “under done it” a bit too much…” However, there was a note at the bottom signed by the doctor. It said something to the effect of: “The patient seemed sincere in his efforts.”

A week or so later the time came to report to Letterman General with my sealed test results. I was shown to another austere army barracks-like warren of small windowless offices. I entered one of these rooms and a U.S. Army Captain stood up and shook my hand. He was young and impeccable in his starched khaki and olive drab officer’s uniform. Good morning, Mr. Stevens. I’m Captain Doctor Krempler (we’ll call him) and I guess you have some medical records for me.” I silently handed over my sealed envelope. The Captain Doctor now held my fate in his hands. He unsealed the envelope and slowly looked through its contents. He didn’t say a word; just nodded slightly a few times. He held an x-ray up to the light and studied it for a few minutes. “This x-ray shows what appears to be an enlarged heart. It may be that the pectum ex cavitum you have may have pushed your heart to the side. I’m more of a lung man, myself. Let me take this down the hall to my colleague who’s more of a cardio guy. Excuse me. I’ll be back in a few.” With that my fate walked briskly down the hall leaving me in my chair, trembling with fear and loathing (apologies to the late Hunter Thompson…)

After what seemed like an eternity, the good doctor returned. He took his place behind his desk, sat down, and looked at the file for a bit more. Finally he stood up; I stood up; he looked across the desk at me; smiled; reached out his hand and said “congratulations!”. My heart sank as I reluctantly took his hand and I thought the worst. He continued, “Mr. Stevens, after reviewing your records, my colleague and I have decided that because of your respiration test and the placement of your heart, based on your x-rays, we are assigning you a draft status of 4-F.” I looked at him in confusion. “Doctor, when you said congratulations, I thought you meant I was qualified to join the army, you being a U.S. Army Captain and all.” He smiled as he withdrew his hand from mind and said. “Gosh no, Stevens. I’m glad to be able to qualify you 4-F. How do you think I came to be here? I was drafted! Now that your free of your draft obligations you go on and have a good life!” And with that I left the building. I do not believe my feet touched the ground till I got to the parking lot.

I jumped into my cranky little Sunbeam Alpine sports car with the top down and drove to Point Reyes where I parked next to a large open pasture of grass. As I ran across the pasture I shouted to the wind and no one in particular, “I’m free! I’m free! Lord God almighty…I’m free at last!” or… words to that effect… For many months the spectre of being drafted into that horribly futile war hung over my head (as I’m sure it did all of us) like the proverbial sword of Damocles. The single hair of a horse’s tail that held the sword aloft had finally broken and the sword lay harmless on the ground beside me. The future was no longer a dark tunnel but a bright sunny day in a green pasture by the sea, pregnant with possibilities. Thank you Captain Doctor Krempler for giving me back my life. That’s my story of confronting the draft; what’s yours? John Landon, thanks again for your wonderful story.

Best wishes to all, Mickey da Mayor of Happy Acres

Here I am preparing for my intended future roll as "Commander Stevens" in charge of the Pacific fleet. Little did I know at the time that that strange indentation in my chest would thwart my bellicose dreams...

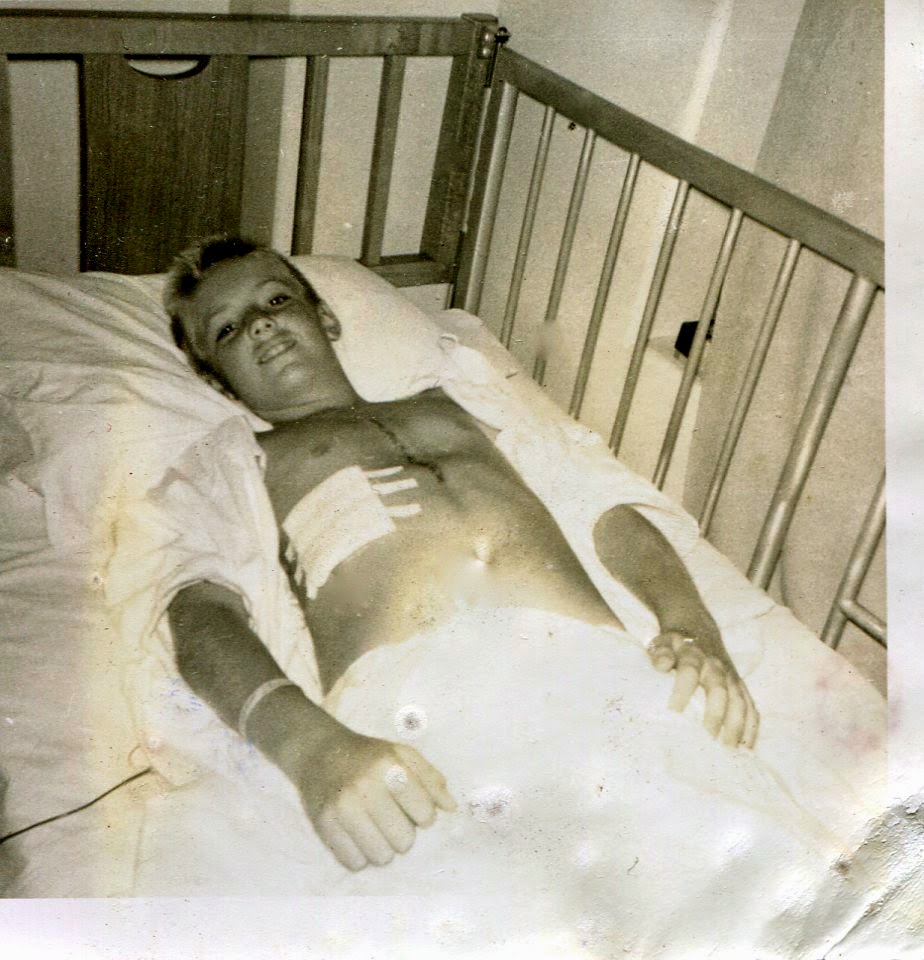

Here I am in Queen’s Hospital in Honolulu in ’59, most likely in a state of drug-induced post-surgical bliss; the scar from my pectum ex cavitum surgery clearly visible along with my indented chest. (It’s sadly ironic that my mother died of cancer in that same hospital six years prior.) I mean really, would you want this toe-headed wastrel in your army? I can imagine what my sergeant would have said, “OK, men! We’re going out on patrol tonite with full bivouac packs! We’re headin’ back up hamburger hill! Stevens! You know the drill. Hide under your cot till we get back at 0500 tomorrow! I'll have no man in my platoon who can't draw a full breath!"

Here I am several years later as young Oliver Twist, the boarding school boy. As I check out the surf in front of a neighbor's house, I see that the scar has faded somewhat but the "pectum cavity" remains. In a year or two chest hair would help obscure my condition.

No comments:

Post a Comment